What is your scientific background?

For my undergraduate education, I went to the University of Pittsburgh on a full-tuition scholarship. My first major was philosophy. I enjoyed the deliberate, organized thinking and it was my first love, intellectually speaking. I was deeply interested in Ethics, but I wanted more concrete answers about problems that seemed like they had been solved by science. Learning how neurons transmit signals was a breakthrough for me, because there was at least a partial answer to the question, “How do our brains work?” I added majors in psychology and history and philosophy of science. I enjoyed all of the intellectual work I had been doing, but at some point, it became clear to me that I was going to graduate and that I hadn’t really thought about what I wanted to do after college.

After a lot of self-reflection, it was clear to me that one of the constants in my life was that I have always been fascinated by animals. If you take me to the zoo, I will be up at the glass with the kids, trying to get a closer view of what the animals are doing. I once spent nearly an hour at the Pittsburgh zoo watching a beaver eat an orange.

For a long time, I thought I wanted to be a veterinarian because that was the only job I knew of where you would work with animals every day. I used the last few semesters of my scholarship to take as many of the required courses for pre-med as I could.

Why did you choose to become a scientist? How did you choose your field of study?

After college, I worked at a vet clinic and applied to vet school. I didn’t get in. By then, the Great Recession had hit; I was not able to afford my health insurance or my student loan payments, so I moved back to Ohio to live with my parents. I applied to the master’s in the biology program at Youngstown State University, which solved a few problems: I could get affordable health insurance and defer my student loan payments while I was in school.

I didn’t have an advisor, I didn’t have a focus, and I didn’t know anyone. I had the immense luck to see a talk by Dr. Michael Butcher about bone loading in Virginia opossums. I made an appointment to meet with Mike, and he suggested that I study digging animals, particularly the American badger. I left his office, went to the library, and took out every book that mentioned American badgers. I found every article about badger digging and badger anatomy. When I met with Mike a week later, I had a three-inch binder full of badger information. I wanted to talk about the colorful descriptions of badgers written by naturalists in the 1920s and about the bone adaptations that made an animal specialized for digging. He took me on as a graduate student on the spot.

I worked with Mike for 2 years. My master’s thesis was about the adaptations in the muscles of American badgers that allow them to generate high forces during digging. I dissected the forelimbs of American badgers mailed to me by Rick Tischaefer at the North Dakota Fur Hunters & Trapper Association.

I love biomechanics and comparative anatomy because I can see my subject with the naked eye. I get to watch the endlessly fascinating things animals do, collect data about them, and try to make sense of it. It’s like I get “paid” to watch beavers eat oranges. I’m not sure I could have been a scientist in any other field.

Which topic are you working on at the moment? Why did you choose this topic and how do you think you’ll make a difference?

After I finished my master’s degree, I moved to Las Vegas to get my Ph.D. with David Lee at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. It was a really big deal for me (and my cats) to move across the country for this, but Dave had a biplanar x-ray video setup which meant I’d be able to watch animals do things more clearly than ever before.

Dave let me pick my project, which is been a study of the biomechanics and morphology of three closely-related desert rodents. All three rodents dig their own burrows in the desert, but they have very different body types. Pocket gophers are short, robust, sausage-shaped digging specialists and pocket mice just look like regular mice. Kangaroo rats have very long hindlimbs and short forelimbs and hop around on their hindlimbs in a way that looks similar to a kangaroo.

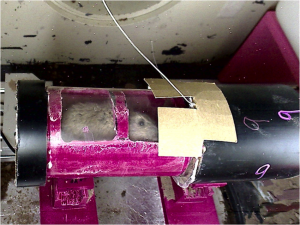

I designed and built my own equipment to measure the forces produced by the animals digging in real substrates, and named it the “Tunnel-tube.” I recorded x-ray video of animals digging in the Tunnel-tube (check out videos at www.biologyunderground.com). I collaborated with Jesse Young and Adam Foster at NEOMED to microCT scan the bones of the rodents I studied and their close relatives. I am currently analyzing those scans and performing 3d morphometric analysis.

What are your biggest achievements, and what are your biggest failures?

Finishing my Ph.D. will be my biggest achievement. I think failure is an enormous part of science that we don’t discuss very much. I failed early and often when attempting to build my tunnel-tube for measuring digging forces. I learned a lot about what was possible from those failures that I wouldn’t have learned if someone had handed me a finished tunnel-tube on day one.

What is a typical day like for you?

Right now, I am analyzing data and writing my dissertation. Because I’m not near my university, I typically work from home. I wake up around 8, drink coffee and eat oatmeal while catching up on news and email. Around 9, I get dressed and go to my office to work on my computer. I work until 2 in the afternoon when I remember to eat something. After that I work until around 5, then take a break until it’s time to make dinner, usually around 6:30. I eat dinner with my husband and we watch Jeopardy! every night. Around 9, I will usually go back to working until 11 or midnight.

What are the hardest parts related to this work?

Working from home has its own unique challenges. The benefits are that I don’t have to spend much time getting ready or commuting, but a drawback is that it can be extremely isolating. The hardest part is that sometimes I really need to talk through an analysis problem with another person to clarify my own thoughts. I have enough to do that when this happens, I can usually write down my problem and switch gears to a different part of the project. I go back to whatever I needed to talk about when my husband is home, when a science friend is online, or when I can talk to my advisor.

Is there any scientific topic (outside of your field of research) that you think should have more scientific attention? Which one?

I would love to see more work on new vaccines and new antibiotics. Both of these innovations have saved millions of lives, but they are not typically profitable for drug companies to produce.

Ok, I have one more, and that is the entirety of basic scientific research, which I realize is huge. There is innate worth in better understanding our universe, but we also don’t know what applications someone may develop using our research in 50 or 100 years. Basic research is an investment in future science.

What is the funniest or most memorable thing that has happened to you while working in science?

One of the best things that happened to me was that I got to work with kangaroo rats. Kangaroo rats get used to being around people quickly and can be very friendly, so it was always a joy to work with them. They also produce very little urine so they are unlikely to pee on you while you are holding them, which I consider being a major bonus.

I also really enjoyed working with the gophers even though they did not like me. They are not as obviously cute as the kangaroo rats, but I kind of liked their attitude. I had to wear thick leather gloves when handling them because they could have easily bitten off part of a finger. (My husband likes to point out that his welding gloves somehow developed a number of tooth marks.) Watching the gophers dig was like watching the Olympics: I got to see them doing what they were born to do incredibly well.

If you were completely free to choose a scientific topic to work on, which would it be?

One of my cats, Harry, has no hip joint on his right side. He has aseptic necrosis of the femoral head, which is fairly common in young, neutered male cats. I would like to study the progression of this disease. I’m so impressed by Harry: he walks, runs, and jumps fairly well. I’d like to use x-ray motion analysis on animals with this disease to see how they compensate for having no hip. However, I’m pretty sure I love cats too much to be able to work on them scientifically.

Do you come from an academic family?

My family is full of teachers, specifically public school music teachers. Both of my parents taught high school and middle school band for their entire careers. My brother grew up to become a high school band director. My grandparents encouraged all their children to pursue higher education and music.

How does your family regard your career choice?

My husband, Larry, is an engineer and loves science, so he is very encouraging of my career. He has built numerous gadgets to help me, including specially designing a cart that I could easily fold up and take with me when setting traps. Larry also came with me on nearly every trapping expedition. My family is supportive and likes to see my work, although they sometimes don’t understand the particulars.

Besides your scientific interests, what are your personal interests?

I love history. I try to fill in the gaps in my knowledge when I notice them, so I have read a lot about the French and American revolutions recently because I didn’t think I knew enough about either. Currently, I am learning about the US civil rights movement.

I also like to make things. I enjoy cross-stitching, sewing, painting, and 3d printing.

What were the biggest obstacles you had to overcome?

I was in an emotionally/psychologically abusive relationship for most of my time as an undergraduate. I wasn’t completely aware that the relationship was abusive until I got out of it, and even still I wasn’t aware of how much it affected me until I started working on my Ph.D. dissertation.

I’d kept myself very busy to avoid addressing my feelings stemming from that relationship. I had struggled with depression and anxiety, but once I had time and space to work on my dissertation, both returned. My psychiatrist diagnosed me with PTSD from the abusive relationship. I had the worst episode of depression I’ve ever had about a year and a half ago.

Through intensive outpatient therapy and medication, I started to pull myself out of the pit of depression. I still see a counselor and take medication but I feel better than I have in years. Confronting my past trauma has made a world of difference.

What (or who) motivated you in difficult times?

My cat Sophie only tolerated two people on earth: my mom and me. Sophie was mean to everyone else, and I knew she would be mad if I ever gave up.

In your opinion, which changes, if any, are needed in the scientific system to be more attractive to female scientists and possible future scientists?

Sexual assault needs to have serious career consequences for perpetrators. Sexual harassment and micro-aggressions need to be taken seriously in scientific settings. I think many people in science think they are too rational and enlightened for sexism or racism or ableism to be a problem. Those people are wrong. We all need to acknowledge our implicit biases. As a woman, there is a huge temptation to be “the cool girl” and go along with it, but that hurts you, the women around you, and any future women your colleagues will interact with.

Representation is hugely important. You need to see someone like you doing something before you can really imagine yourself doing it. As a white, cis-gendered, heterosexual woman, I was able to see people like me doing science sometimes. But women of color have fewer opportunities to see themselves represented in the scientific community. That needs to change. And of course, there are so many identities that are not visible. LGBTQ+ people are often not visible or out, nor are those who suffer from mental illness. Survivors of domestic abuse, sexual assault, and rape are not visible, but they’re there. We need to recognize the human side of scientists and be honest about who we are. That’s how we reduce stigma.

If you had the option to give advice to a younger version of yourself, what would that be?

- Leave that guy earlier.

- Go to the dentist.

- Don’t dye your hair red.

Lexi can be contacted via Leximoore@gmail.com or twitter, and you should check out her website!