What is your scientific background?

I am originally from coastal British Columbia in Canada. I did my undergraduate degree at Capilano College and the University of Victoria. During my undergraduate I spent quite a bit of time at Bamfield Marine Sciences Center, a remote marine research station on the west coast of Vancouver Island. It’s hard to imagine a more picturesque learning environment – eagles swooping for fish from the library, kayaking across a beautiful passage to get to your field class, and late nights researching on the beach. It was here that my interest in research got started. I learned the upsides and downsides of science, where an early winter storm can easily destroy months of work.

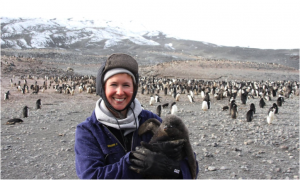

After graduation I spent a few months in South America, where I was a field technician in Argentina and Ecuador, helping with ornithological projects. Then I started my masters, which was based out of Memorial University of Newfoundland, where my research took place in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska. In this remote setting, surrounded by millions of seabirds, my research career began. I was interested in nocturnal, burrow-nesting seabirds (storm-petrels and murrelets), and how they recover after invasive foxes are removed. Across the Aleutian Islands, arctic foxes were introduced for the fur trade, decimating populations of seabirds. For the past few decades, the USFWS have systematically removed foxes from islands across the Aleutian archipelago. Although many seabird populations are known to have benefitted from fox removal, little is known about the response from nocturnal seabirds, which are difficult to survey using conventional methods. I tested a new method of monitoring – using acoustic recording to capture night-time vocalizations. I then started my PhD research in New Zealand, at the University of Otago. I was interested in a similar topic – how seabirds recover after the removal of invasive predators, but at a larger scale. I wanted to examine the recovery process in order to prioritize restoration techniques after predator removal. For example, can we just leave seabirds to recover passively, or do we need additional active methods for seabirds to return to an island? After my PhD I spent a few months studying penguins in Antarctica. I’m now a postdoctoral research fellow at Colorado State University where I study acoustic ecology (a field of study which I began during my masters).

Why did you choose to become a scientist?

I have always been a curious person – I always wanted to be a ‘student for life’. I chose to become a scientist when I discovered that being a scientist meant you could get paid to ask and answer questions about the natural world.

How did you choose your field of study?

I’ve always been fascinated by animals but studying birds and marine biology really piqued my interest. Seabirds seemed like a natural way to combine these two topics. When I started my master’s research in the Aleutian Islands we spent a few nights on Buldir, an undisturbed seabird colony (the most diverse seabird colony in the northern hemisphere). As soon as the sun went down the sound of nocturnal seabirds calling was deafening, which gave me an appreciation for acoustics.

Which topic are you working on at the moment? Why did you choose this topic and how do you think you’ll make a difference?

At the moment I am working in a field called ‘soundscape ecology’. A ‘soundscape’ is a similar concept to a ‘landscape’, where all the biological, geological, and human sounds that emanate from a landscape reflect the ecological processes occurring on a landscape. Using recordings of sounds across different landscapes we can monitor changes in biodiversity and examine the impact of human noise. At the moment we have a whole variety of conservation-related projects – mapping noise pollution in parks across the United States, examining the effect of motorcycle noise on prairie wildlife, and identifying the diversity of birds in areas with different fire treatments to name a few.

Did you have a role model that influenced your decision to work in science?

Absolutely, I can say without a doubt that the person who inspired me to pursue a career in science was my second year zoology teacher Marja de Jong Westman. During my first two years of college I was determined to pursue a pre-medical degree and take my MCAT exams. However, after the first few months of Marja’s class, when she took us bird watching, intertidal exploring, and generally shared her enthusiasm for the natural world – I took a hard turn, falling in love with zoology. Marja ignited my curiosity for the natural environment and my passion for conservation biology. There are few people in our lives who have such a contagious enthusiasm, I was lucky to have my path altered in such a positive way.

What are the hardest parts related to this work?

Long days at a computer are a new challenge for me. I’m comfortable with working long hours in the field – hiking with a heavy pack, putting up with freezing temperatures, and living in remote camps. However, I find writing and coding all day far more difficult, especially staying focused and completing frustrating tasks.

What are your biggest achievements, and what your biggest failures?

My proudest achievements are graduating my Ph.D. with honors and publishing a paper in Science magazine. I’m not sure I could name a ‘biggest failure’, although many small things seem like ‘big failures’ at the time – a paper getting rejected, not collecting that last transect of data.

Did you ever doubt your abilities as a scientist? Why? How did you handle these situations/feelings?

Absolutely, almost every day. From what I gather, feeling inadequate is a fairly normal part of being a scientist, especially an ecologist. The ecological world is extremely complicated, thus, trying to decipher patterns or break down processes can undoubtedly make you feel foolish. However, these feelings are often overshadowed by scientific breakthroughs. You master a new technique, understand a new concept, or discover an interesting new pattern and much of these feelings of incompetence are replaced by joy.

What (or who) motivated you in difficult times?

My love for what I do always pushes me to keep going. Also, my amazing husband, group of friends and parents are always there for support.

In ten years, what do you hope to have accomplished in terms of your work?

Acoustic recordings show great promise as a method of monitoring biodiversity at a large scale. Recording devices can collect acoustic data in many places at the same time, capturing the diversity all vocalizing animals (e.g. birds, frogs, insects) across a landscape, or even a continent. I hope that in 10 years we learn how to rapidly extract meaningful biological information from these enormous acoustic recording datasets. This way we can readily apply this powerful technology to answer conservation questions at huge scales – e.g. how do different types of human threats interact to affect biodiversity? How effective are different restoration or mitigation techniques?

Also, one of my favorite parts of my job is mentoring young scientists, supervising their theses or teaching acoustic skills. In 10 years, I hope to have mentored a long list of keen young scientists who go on to have successful careers in ecology.

Is there any scientific topic (outside of your field of research) that you think should have more scientific attention? Which one?

Addressing people’s perception of nature and examining society’s motivation to change their habits are extremely important aspects of conservation biology. In my opinion, this intersection between sociology and conservation biology deserves more scientific attention. For example, many Americans do not believe that climate-change exists, resulting in limited funding for projects that could alleviate or plan for climate-change-related impacts. Examining why some Americans do not accept climate-change facts and what could be done to change this perception is integral to motivate social change. Figuring out how to keep an increasingly urbanized global population connected with nature is an area of study I would love to work on.

What is the funniest or most memorable thing that has happened to you while working in science?

The most memorable event is likely a situation in the Aleutian Islands, which happened during the first field season of my masters. In the Aleutians there are two-person field crews on several islands across the archipelago. In order to stay safe, each crew checks in by radio twice a day. Because you spend the entire summer on an island with one other person – those radio check-ins can be the most exciting part of your day. We noticed that over the course of the summer, the camp on Kasatochi kept reporting earthquakes. These are fairly common in the Aleutians, because the islands are volcanic. However, we hadn’t felt any earthquakes, so we were getting jealous of Kasatochi. Towards the end of the summer, Kasatochi was reporting several earthquakes a day, making us even more jealous! Eventually, Kasatochi reported earthquakes each 20 minutes and smoke coming from the caldera in the middle of the island… followed by ‘mayday’ calls over the radio… their island was erupting! Luckily a fishing vessel answered their mayday calls, because as they pulled away from the island there was a 50,000 ft ash plume in the sky and the entire island was covered in pyroclastic flow.

Do you come from an academic family?

No, quite the opposite, I come from a very blue-collar family. My mom was a postal worker and my dad was a carpenter. I’m the first in my immediate family to receive a Ph.D. However, I come from a very hard-working family, lots of farmers. Hard work and motivation are both key elements in science which were passed on to me from my family.

How does your family regard your career choice?

They couldn’t be more proud and supportive.

Besides your scientific interests, what are your personal interests?

I love photography and traveling, particularly a combination of the two. On weekends, my husband and I are often in the mountains, camping, hiking, and taking pictures. I also love music and art – I try to catch as much live music and visit as many galleries as I can.

Is it hard to manage both career and private life? How do you manage both?

I don’t find it particularly difficult; however, I have a very supportive husband. I think that making your personal life a priority helps with balance. Making hard boundaries, for example – switching off from work at 5 pm at least 3 days a week is my current goal. Also, taking full breaks (with no email checking or work-related reading) is imperative, not only for your personal life but also to rejuvenate you for work.

What is a typical day like for you?

In the past I used to spend most of the summer in the field, collecting data in remote field stations. These days, a typical day is spent at the office at the computer – either writing or computer modeling. My day might include meeting with my students to help them with their research project or meeting with scientists at the National Parks Service to discuss park projects. I just got back from a research trip to southern India, where I spent a few weeks collaborating with other acoustic ecologists and collecting recordings in the field.

What were the biggest obstacles you had to overcome? Did you ever have the impression that it would be easier/harder if you were male?

The biggest obstacle for me has been developing my confidence and being assertive. Realizing and acknowledging your expertise can be challenging for women in science. It’s important to assert that you are an expert and have an important perspective to share, despite some people trying to dismiss your knowledge. I think that having my work recognized would be easier if I were male. Some (not all!) male scientists tend to be more assertive, promoting their work more confidently, which is great for getting them and their work recognized. Also, I feel that teaching would be much easier if I was male. I think students are much harder on female professors, readily pointing out their mistakes and shortcomings.

What kind of prejudices, if any, did you have to face? How did that make you feel? Were you able to overcome these?

There are many ways that people inadvertently minimize women in science. For example, there have been several situations where my hard work and accomplishments were met with adjectives like “lovely” and “sweet”, rather than “thoughtful” or “intelligent”. Also, although these situations were rare, doing field work tends to bring out a certain level of machismo and can lead to inappropriate comments.

In your opinion, which changes, if any, are needed in the scientific system to be more attractive to female scientists and possible future scientists?

A departure from the old system, where academics were encouraged to work 24/7, to a focus on the importance of maintaining a healthy personal life. Especially for women who have a family, the emphasis on working extreme hours and producing a high output at all costs is damaging and unreasonable. Also, we need to start taking into account maternity leave for scientists. A hole in your resume from maternity leave (or paternity leave for that matter!), is still considered a disadvantage, which is outrageous.

If you had the option to give advice to a younger version of yourself, what would that be?

Don’t sweat the small stuff. Something that seems like a total ‘disaster’ right now may not even be memorable in a few years.

You can contact Rachel at Rachel.Buxton@colostate.edu, and follow her on Twitter!